-

Architects: Hopkins Architects and Centerbrook Architects and Planners: Hopkins Architects Design Architects and Centerbrook Architects and Planners, LLP Executive Architect

- Area: 68800 m²

- Year: 2009

-

Photographs:Morley von Sternberg

Text description provided by the architects. Kroon Hall School of Forestry & Environmental Studies is Yale University's Greenest Building. Chosen as a 2010 AIA/COTE Top Ten Green Project the ambitious goals for Kroon Hall encompassed taking a brownfield site crowded by looming and gloomy brownstone edifices – an area replete with dumpsters, pavement, and an aging power plant – and establish a building that would bring light, openness, and a connection to the natural world.

Follow the break for drawings and photographs of this project.

Project Team: (Centerbrook) Mark Simon, FAIA, James A. Coan, AIA, LEED AP, Theodore C. Tolis, AIA, LEED AP, David O’Connor, Nick Caruso, Sheryl Milardo, Sue Pinckney, Barbara Kehew, Sue Savitt, Steve Haines; (Hopkins) Sir Michael Hopkins, Michael Taylor, Sophy Twohig, Henry Kong, Thomas Corrie, Tom Jenkins, Andrew Stanforth, Nate Moore, Edmund Fowles, Laura Wilsdon, Kyle Konis, Rose Evans, Martyn Corner

Structural, Mechanical, Electrical, Plumbing, and Fire Protection Engineers: ARUP

Gus Speth, Dean of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, wanted to build the greenest building on the planet. The flagship of Yale University’s sustainability mission, Kroon Hall is designed to use 58 percent less energy than a comparable peer.

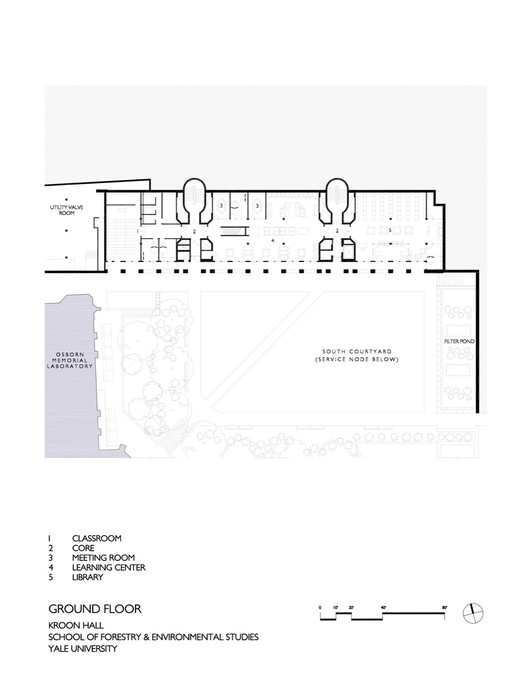

A narrow, curved-roof rectangle built of stone, concrete, steel, and glass, Kroon is set between two existing science buildings, forming two new grassy courtyards, and taking the place of an aging power plant on a brownfield site. The LEED Platinum building provides bright modern company for an Eero Saarinen building across the street in a neighborhood awash in dark, neo-Gothic edifices. Centerbrook Architects and Planners, as Executive Architect, collaborated on the project with the Design Architects, Hopkins Architects of London along with an all-star team of consultants that included ARUP engineers, atelier 10, Nitsch engineering, Kalin Associates, and Olin Partnership.

The new home for the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies (FES) also needed to make an unmistakable statement about the commitment of both the FES and Yale to sustainability and environmental stewardship. It would change the way the university built buildings, and hopefully inspire and challenge other institutions as well.

A modernist blend of a cathedral nave and a Connecticut barn, the building is long and thin, sited to admit heat (from above and below ground), daylight, and air – as well as to create outdoor spaces for practical and aesthetic purposes. Ohio sandstone exterior walls connect Kroon to similarly clad colleagues on the main campus, while the fir louvers on either glass end of the building announce a new and practical aesthetic.

The honey-colored Kroon cheers up its neighborhood considerably, in part, with a broad welcoming outdoor lobby facing the street, while a walkway nearby lures pedestrians into an expansive courtyard (one of two new greenswards) that does double duty as a green roof above a new service node for the entire Science Hill’s campus. At the far end of the courtyard, perambulators pass a rain garden stocked with floating rafts of wild rice, iris, and cattails, which combine to purify Kroon’s rainwater runoff that feeds this artificial wetland. From here, due east of the building, the mature hardwood canopy of Sachem’s Woods beckons travelers into the heart of Science Hill.

The approach to achieving a 58 percent energy reduction for Kroon Hall, or 26.7 kBtu/Sf./Yr., was to first examine ways to minimize its energy requirements through siting and use of building form, materials, and envelope to enhance energy gain as well as energy retention and natural ventilation. For example, the building’s long and thin shape was designed to maximize southern exposure for passive warmth and natural lighting throughout the interior while serving as the ideal orientation for both photovoltaic panels on the roof and hot-water solar units embedded in the wall. Sensors add just enough artificial wattage only when daylighting falls below suitable levels. The stone walls and exposed concrete interior building mass serve to retain heat in winter and cold air in summer.

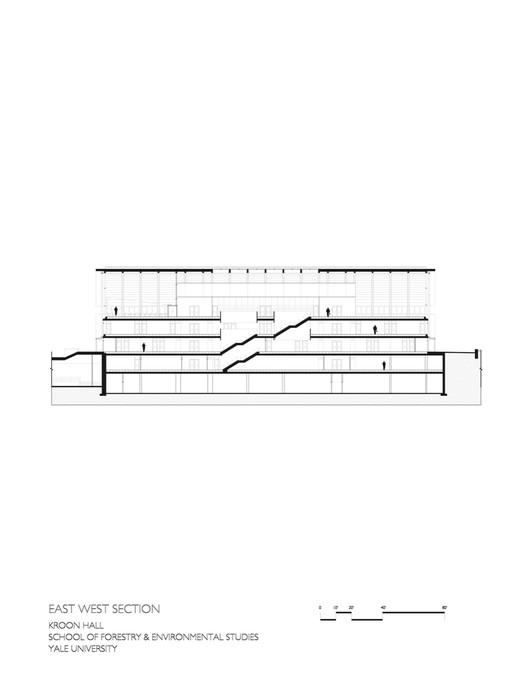

The stacking of the floors with a central staircase also facilitates natural air flow as do air plenum and multiple diffusers in the elevated floors. Building occupants participate, as well, controlling operable windows as sensors that alert them to optimum times to open or close. Designed for natural ventilation, Kroon did not require the energy-intensive mechanical systems of conventional buildings.

With the need for energy thus lowered, architects turned their attention to the bells and whistles of green design, the 100-kilowatt solar photovoltaic array on the roof that generate 23 percent of the building’s energy, solar hot water units on the south wall, and the geothermal pump. These account for 6.09 kBtu/Sf./Yr.

Virtually every opportunity to save energy and build sustainably was pursued. Potable water use is reduced to 81 percent below baseline through conservation plumbing features. The red oak paneling, which contrasts nicely with the large swaths of exposed interior concrete, was harvested from Yale’s own sustainably managed forest in Connecticut. Paperless communication among the architects and far flung consultants from Abu Dhabi and London to New Haven saved more than $100,000 in reams of paper, time, and delivery costs.

Finally, the Kroon Hall’s design accommodates Yale’s campus-wide transportation system and helps to rationalize its delivery and recycling infrastructure. On a micro scale, it provides spaces for the growing cadre of bicycle commuters.

Kroon accomplishes all while affording arresting, modern architectural company for its neighbor across Prospect Street – Eero Saarinen’s swayed-back hockey arena known as the “Yale Whale.” For half a century, this curvaceous cetacean swam alone in its stolid neo-Gothic neighborhood. Now it can cavort unselfconsciously with its new, curved-roofed, 21st century colleague with all that sunlight bouncing off its walls.